As the Allston Family Began to Reestablish Their Lives After the Civil War, They Found That

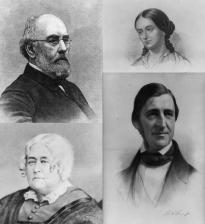

Those Americans who have heard of American Transcendentalism associate information technology with the writers Ralph Waldo Emerson and his friend Henry David Thoreau. Asked to name things about the group they remember, well-nigh mention Emerson'south ringing declaration of cultural independence in his "American Scholar" address at Harvard's commencement in 1837 and his famous lecture "Self-Reliance," in which he declared that "to be keen is to exist misunderstood"; Thoreau'southward two-year experiment in cocky-sufficiency at Walden Pond and his advice to "Simplify! Simplify!"; and the government minister Theodore Parker'due south close association with the radical abolitionist John Dark-brown. But Transcendentalism had many more participants whose interests ranged beyond the spectrum of antebellum reform.[ane]

Those Americans who have heard of American Transcendentalism associate information technology with the writers Ralph Waldo Emerson and his friend Henry David Thoreau. Asked to name things about the group they remember, well-nigh mention Emerson'south ringing declaration of cultural independence in his "American Scholar" address at Harvard's commencement in 1837 and his famous lecture "Self-Reliance," in which he declared that "to be keen is to exist misunderstood"; Thoreau'southward two-year experiment in cocky-sufficiency at Walden Pond and his advice to "Simplify! Simplify!"; and the government minister Theodore Parker'due south close association with the radical abolitionist John Dark-brown. But Transcendentalism had many more participants whose interests ranged beyond the spectrum of antebellum reform.[ane]

To empathise information technology fully, however, one must consider its origins. Transcendentalism's roots were in American Christianity. In the 1830s immature men grooming for the liberal Christian (Unitarian) ministry chafed at their spiritual teachers' belief in Christ's miracles, claiming instead that his moral teachings lone were sufficient to make him an inspired prophet.[two] Similarly, they rejected the widely accustomed notion that man'south cognition came primarily through the senses. To the reverse, they believed in internal, spiritual principles as the basis for man's comprehension of the world. These formed the basis of the "conscience" or "intuition" that fabricated it possible for each person to connect with the spiritual world. When homo thus moved higher up or beyond—"transcended"—the cares and concerns of the mundane, lower sphere, he was in touch with and lived through this spiritual principle, what Ralph Waldo Emerson termed the "Oversoul."[three]

At its core, Transcendentalism celebrated the divine equality of each soul. In that location was no arbitrary division between saved and damned, for anyone could accept a transcendent experience and thereafter live his life connected to the spiritual world. Transcendentalism thus seemed the platonic philosophy for a nation dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal and have the aforementioned inalienable rights. In this, the motion began to overlap with antebellum efforts toward social reform, for if all men and women were spiritually equal from nascence, they all deserved to be treated with social and political equality equally well.

Because of this bones belief, many Transcendentalists became involved in efforts to contrary weather condition that prevented individuals from realizing their total potential. For example, Bronson Alcott, Louisa May Alcott's male parent, began the Temple School, an educational experiment for elementary-age children that stressed their innate divinity and encouraged its early on discovery and tillage. He had to shut the school later on parents objected to how Alcott taught the Gospels. Alcott'south assistant there, Elizabeth Peabody, went on to pioneer the kindergarten movement in the U.s.a.. Orestes Brownson, son of Vermont farmers and one of the few Transcendentalists not college-educated, remained loyal to his roots and dedicated his life to improving the conditions of the working class; his statements on the likelihood of grade warfare betwixt laborer and owner anticipated those of Karl Marx.

Other Transcendentalists moved directly toward what nosotros would recognize today as socialism. Brownson's close friend George Ripley resigned from his Unitarian pulpit about the Boston waterfront and started the Brook Farm Institute of Agronomics and Teaching. Through this utopian experiment in communal living he tried to pause down the barriers between intellectuals and laborers, and divided the customs's profits according to socialist principles. At Brook Subcontract members rotated through dissimilar forms of work, the most educated having their turn at farming, husbandry, and crafts, and common laborers given the opportunity to engage in art, music, drama, and other activities to which they had been little exposed.[4] Alcott, seeking a new projection after the failure of the Temple School, began the quixotic Fruitlands experiment in Harvard, Massachusetts, where he and a handful of other idealists sought to alive as vegetarians, giving upwards fifty-fifty shoe leather and beasts of brunt in their respect for all life. The "customs" did non last through its first autumn.[v]

In another arena, Margaret Fuller, influenced by Emerson'southward doctrine of self-reliance, became the foremost advocate of women's rights in her day. Her pioneering Adult female in the Nineteenth Century (1845), in which she argued, on Transcendentalist principles, the economic and psychological equality of the sexes, influenced many Transcendentalists and others. Not afraid to put her principles into operation, she later traveled to Europe to report on the political and social revolutions of 1848 for Horace Greeley'south New-York Tribune; she and her husband, an Italian count, died in a shipwreck sailing from Europe to the United States in 1850.

For some, such reform activities were the natural outgrowth of Transcendentalist thought, and they made social reform virtually the unabridged focus of their Transcendentalism. Until the 1840s Emerson was not the de facto leader of the group. Rather, the most visible members of the loosely associated grouping were Ripley and Brownson, both of whom stressed social date in their Unitarian ministries in Boston.

The impoverished, the mentally and physically challenged, the imprisoned and those otherwise institutionalized, and the enslaved: Transcendentalists recognized these members of society as their equals in spirituality, and America's hope would not be fulfilled until the benefits of its citizenship were available to all. Ripley's Brook Subcontract was the almost dramatic attempt to resolve the inequities in the mundane world. He abandoned his ministry amongst middle-class Bostonians in large measure out considering his congregation was content in their condolement and felt no compulsion to extend understanding and charity in the mode their government minister wished. Similarly, Brownson, appalled at what he saw as the rapidly deteriorating social status of the working class, start started his own reformist periodical, the Boston Quarterly Review, and then embraced Roman Catholicism, whose ethic of brotherhood he believed ameliorate served the impoverished and oppressed.

Ripley's and Brownson's centrality began to fade when Emerson emerged as a major Transcendentalist spokesperson in the wake of the furor over his "Divinity Schoolhouse Address" (1838), when he insulted the Harvard theological faculty past claiming that their preaching was uninspired, and the publication of his first volume of essays iii years later on. In these and other works he provided Transcendentalists another style to define and act on their behavior, one that revolved around his glorification of the individual rather than active appointment in social reform. Emerson, for example, never joined Brook Farm, although his close friend and cousin Ripley implored him to do so, enlightened that Emerson's participation would bring the experiment even more attention. He wrote Ripley a blunt refusal, explaining that he still had far to travel on his own personal, spiritual journey before he could get so straight involved with other the reformation of others' lives. Centrolineal with Emerson in this belief that self-reform trumped social engagement was his disciple Henry Thoreau and, for a while, Margaret Fuller. Both stressed the importance of private responsibility and attention to one's own conscience rather than amelioration of others' conditions, potentially a distraction from self-improvement.

This separate among Transcendentalists did not get unremarked. Peabody, for example, wondered if Emerson's stress on self-reliance and individual fulfillment might not pb to what she termed "ego-theism," his setting up himself, or comparably inspired individuals, as somehow gods themselves. She concluded that when 1 held such cocky-centered views every bit Emerson did, "faith commit[ed] suicide" when an individual failed to realize that "human being proves but a melancholy God" in comparison to the divine being whom she nevertheless worshipped.[6] Similarly, after reading Emerson'sEssays: First Series, one of Fuller's protégés, Caroline Healey (Dall) thought that what he had to say about cocky-reliance was "improvident and unsafe."[7] Another of Emerson'southward friends, Henry James Sr., echoed this criticism. "The curse of our present times, which eliminates all their poetry," he observed of his contemporaries' resistance to socialism, is the "selfhood imposed on the states by the evil world."[eight]

Emerson himself recognized the disharmonize. Asked to speak at a memorial for the great reformer Theodore Parker, who had died on the threshold of the Ceremonious State of war, he demurred, remarking how different they were in their approaches to the problems of the age. "Our differences of method and working," he wrote to the organizing commission of the memorial, were "such equally really required and honored all [Parker'due south] Catholicism and magnanimity to forgive in me." In the privacy of his periodical, he was even more than candid. "I tin can well praise him [just merely] at a spectator'southward altitude, for our minds & methods were unlike—few people more than unlike."[9]

Through the 1840s this division persisted among Transcendentalists and associated groups, just in the adjacent decade it gradually ceased to be of great significance. Later on the signal year 1850, in which Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law, all parties pulled away from internecine squabbling equally the sectional crisis challenged all Americans to confront the immense trouble of chattel slavery. Transcendentalists who had avant-garde social reforms that included efforts to increment rights for women, labor, and the indigent redirected their energies toward extinguishing the institution of slavery.

Theodore Parker was the leader in this fight, merely he was a special example, for even as he vociferously condemned the Southern slaveholders and the politicians they elected (and whatever northerners complicit with them), he continued to preach about the great inequities of wealth in cities like Boston. He understood the connections between northern businessmen and southern slaveholders, and declared worship of Mammon—or wealth—the evil. In one sermon he told his audience that he was speaking in a urban center "whose most pop idol is mammon, the God of God; whose Trinity is a Trinity of Coin!" "The Eyes of the North are full of cotton," he continued. "They encounter nothing else, for a web is earlier them; their ears are total of cotton, and they hear nothing but the fizz of their mills; their mouth is total of cotton, and they can speak audibly but ii words—Tariff, Tariff, Dividends, Dividends."[10] He genuinely worried that freedom might fail. If men continued to enforce the Fugitive Slave Police force, he said, he did not know when the struggle would end simply did not intendance if the Union went to pieces.

Other Transcendentalists were similarly swept up in this fervor, believing slavery the great evil to exist extinguished earlier all others. Many women who hitherto had devoted themselves to women's rights were swayed by such arguments and believed that their turn for equality would come afterward the African Americans'. Unfortunately, in this they were disappointed. Speaking of the Transcendentalists' commitment to abolitionism in the 1850s, the Unitarian clergyman Octavius Brooks Frothingham explained in 1876 why they and others were so quick to put aside other pressing issues. He recalled that in the 1850s the "agitation against slavery had taken hold of the whole country; it was in politics, in journalism, in literature, in the public hall and parlor."[11]

When the Civil War was over, what became of the movement? Some of its leaders did not even alive to see the end of the war, near notably Parker, Thoreau, and Fuller. Others moved on to new causes. Later on the failure of Brook Farm in the late 1840s, Ripley moved to New York Metropolis, replacing Fuller as book reviewer at Greeley'sTribune. Brownson became an apologist and proselytizer for Roman Catholicism. Peabody embraced the kindergarten movement and, later on, Native American rights. That left Emerson every bit the public face of Transcendentalism.

At that place was some progress in the area of women's rights, with Caroline Healey Dall assuming Fuller'south place as one of the intellectual leaders of the women'south motion, and Brook Subcontract alumna Almira Barlow providing it new guidance. Ministers like John Weiss (Parker's disciple), David Wasson, and Samuel Johnson, all the same, defended Transcendentalism confronting the ascent of the scientific method that placed well-nigh value on cloth facts rather than spiritual ideals. Few Transcendentalists, however, were involved in the growing disputes between labor and capital, the reformation of asylums and penitentiaries, or other matters on a reformist agenda.

By the 1870s, the uneasy remainder between the self and guild that had characterized the antebellum stage of the Transcendental movement tipped irrevocably in the management of the self. The intellectual power of Transcendentalists was directed toward individual rights and, implicitly, market capitalism, non humanitarian reform. Emerson's admittedly enervating philosophy of cocky-reliance, an artifact of the early 1840s, was simplified and adopted as a main principle. More than and more, people identified Transcendentalism with the idea of individualism lone, rather than with the ethic of brotherhood that was supposed to accompany it, a procedure that only accelerated after Emerson's death in 1882. It was left to others to promulgate a religion, the Social Gospel, that reached out to the poor and forgotten.

The New York Unitarian clergyman and erstwhile Transcendentalist Samuel Osgood summed this up well. Reacting to a suggestion that in the 1870s Transcendentalism had lost its relevance, he argued that the grouping'due south very success in spreading its ideas had made their philosophy less visible. "The sect of Transcendentalists has disappeared," he wrote, "because their light has gone everywhere."[12] He meant that American culture had captivated Emerson's near distinctive thought, the deification of the individual. With more than hindsight, however, one might debate differently. Emerson'southward fame presaged, ironically, the death knell of the higher principle of universal alliance for which Transcendentalism, more than any other American philosophy, might have provided the foundation.

[ane] Philip F. Gura, in American Transcendentalism: A History (New York: Hill & Wang, 2007) offers a thorough cursory overview of the subject.

[2] William R. Hutchison, The Transcendental Ministers: Church Reform in the New England Renaissance (New Oasis: Yale Academy Press, 1959), is even so the best source for the religious roots of the controversy betwixt younger and older Unitarians.

[3] Emerson makes the distinction between the Reason and Understanding in his "Divinity School Address" of 1838. He speaks of the Oversoul in 1841 in the essay by that name.

[4] Run across Sterling F. Delano, Brook Subcontract: The Dark Side of Utopia (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004).

[5] See Richard Francis, Fruitlands: The Alcott Family and Their Search for Utopia (New Haven: Yale Academy Press, 2010).

[6] Elizabeth Peabody, "Egotheism, the Atheism of Today" (1858), reprinted in idem., Last Evening with Allston and Other Papers (Boston: D. Lathrop, 1886), three.

[7] Helen R. Deese, ed., Selected Journals of Carline Healey Dall, in Massachusetts Historical Club, Collections 90 (2006), 81.

[8] Henry James, Moralism and Christianity; or, Human being'south Feel and Destiny (New York: Redfield, 1850), 84.

[9] Ralph Waldo Emerson to Moncure Daniel Conway, June 6, 1860, in Ralph L. Rusk and Eleanor One thousand. Tilton, Letters of Ralph Waldo Emerson, 10 vols. (New York: Columbia University Printing, 1939–1995), 5: 221; and Emerson, Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks, ed. William H. Gilman, et al., 16 vols. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960–1982), 14: 352–353.

[10] Theodore Parker, A Sermon of War (1846) in The Collected Works of Theodore Parker, ed. Frances Power Cobbe, 12 vols. (London: Trüber, 1863–1865), 4: 5–6, 25.

[11] Octavius Brooks Frothingham, Transcendentalism in New England: A History (New York: Putnam, 1876), 331.

[12] Samuel Osgood, "Transcendentalists in New England," International Review 3 (1876), 761.

Philip F. Gura is the William S. Newman Distinguished Professor of American Literature and Culture at the Academy of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His books includeAmerican Transcendentalism: A History (2007), which was a finalist for the National Volume Critics Circle Award in nonfiction, Jonathan Edwards: America'due south Evangelical (2005), andThe Wisdom of Words: Language, Theology, and Literature in the New England Renaissance (1981).

gaskinsocapturpon1980.blogspot.com

Source: https://ap.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/first-age-reform/essays/transcendentalism-and-social-reform?period=5

0 Response to "As the Allston Family Began to Reestablish Their Lives After the Civil War, They Found That"

Post a Comment